The second installment of Housing the Human took place on November 2 at Yapı Kredi Cultural Center in Istanbul, as part of the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial. The experts invited to the public forum included Meriç Öner (SALT), Hülya Ertaş (XXI), Moira Valeri (Yeditepe University), Nicholas Korody (Archinect, ED), and Daniel Perlin (Make_Good). Josephine Michau, the founder of Copenhagen Architecture Festival; Freo Majer, artistic director of Forecast and Housing the Human; and Jan Boelen, the curator for this year’s Istanbul Design Biennial, were also present. The projects that dwell on specific and interdisciplinary problem-solution-research processes regarding the vast subject of housing/dwelling was presented to the public, with an impressive audience turnout.

The five selected designers’ proposals have developed rapidly since the last presentation, which was held in Berlin on October 13. The prevailing concepts are shared spaces, efficient use of space and materials, and sustainability in changing economic systems. The projects foresee modes of housing and shelter in future economic conditions. They deal with consumerism and an unnecessary abundance of production via unsustainable methods that will affect the natural and societal world for the worse, and try to gently nudge people into considering alternatives to this depleting mode of living.

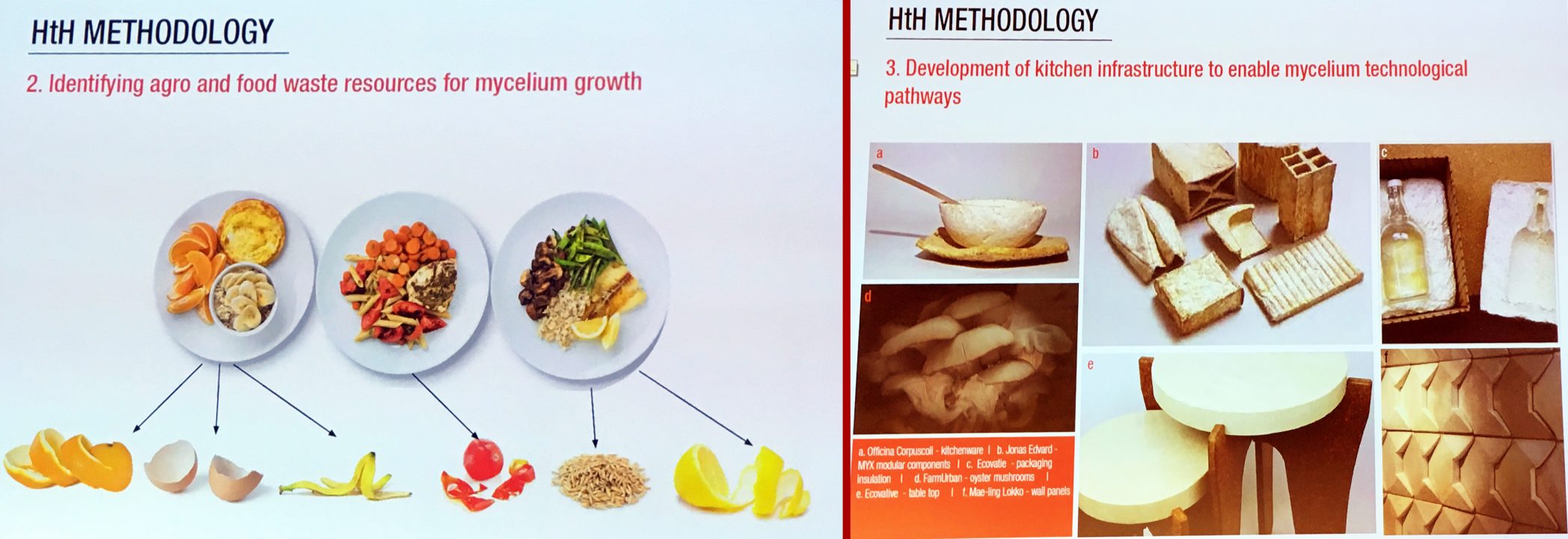

Can the waste from agricultural products that pass from farms to factories into kitchens be further transformed into new products? Can this conversion behavior be instilled as a habit? How does the public access this method easily and democratically?

Mae-Ling Lokko’s Agrocologies is going full steam ahead, with the aim of producing a kitchen prototype using agro-waste and mushroom mycelium. It involves upcycling some of the most underutilized resources, agro-waste and food waste. It also encourages consumers to have agency, to transform the organic waste they individually or collectively produce into another functioning product. In doing this, the upcycling process can be applied not only on an industrial scale or at manufacturing plants, but on the domestic scale as well. The research defines the kitchen as the home’s energy source and social hub and through this intends to design a kitchen unit using the mycelium cycle.

The design process includes subjects such as the effect of bioadhesive mycelium on the biochemical value of food waste, ways of utilizing food’s surplus value, the upcycling process as a new household chore, the allocation of responsibility within the household (man-woman-child) and its impact on family dynamics. Lokko hopes to have designed an interactive, mobile kitchen prototype by the next event, with maybe an accompanying cookbook. She also wants the result of this project to go beyond Housing the Human, believing that sharing the knowledge is essential. She thinks that projects like hers will help dispel the skepticism around natural materials. In the near future, when resources are scarce, projects that investigate alternative ways of production and recycling/upcycling are imperative. Agrocologies may be effective research that can easily be adopted into daily life.

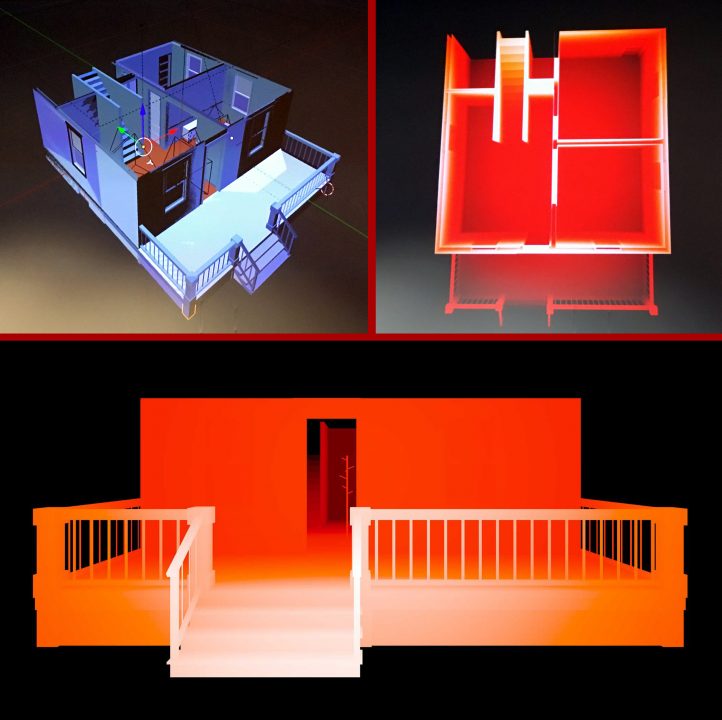

How does a robot perceive a home environment and accept it as its living space? How does it learn what a home environment is? How does it learn what a human is?

Simone C. Niquille’s visual-cultural research Regarding the Pain of SpotMini takes its name from Susan Sontag’s 2003 essay Regarding the Pain of Others and the Boston Dynamics robot called SpotMini created for domestic use. The research is essentially an examination of the extensive databases created for teaching robots their environment, and how that affects their (or anything post-human’s) perceptions of space and objects they encounter, an extension of Niquille’s previous work. Niquille has produced a computational model of the prototype house that was used in the Introduction video for SpotMini using the depth map form, while also mapping 3D objects present in shared open-source databases such as SketchUp 3D Warehouse.

Databases can be considered a subjective portrait of reality from the perspective of the creator of any given model. The objects placed in a space, the classifications of those objects, the subjectivity and glitches behind those classifications alter the perceived environment. Simone sees her project as an archeological research that predicts various future problems and crises. She’s concerned with idealistic assumptions about what a house is and what occupies that space. The project’s origin is not digital; she says that “it seems so shiny and futuristic but it is medieval.” SpotMini is just a character in this research, there are greater questions behind its pain.

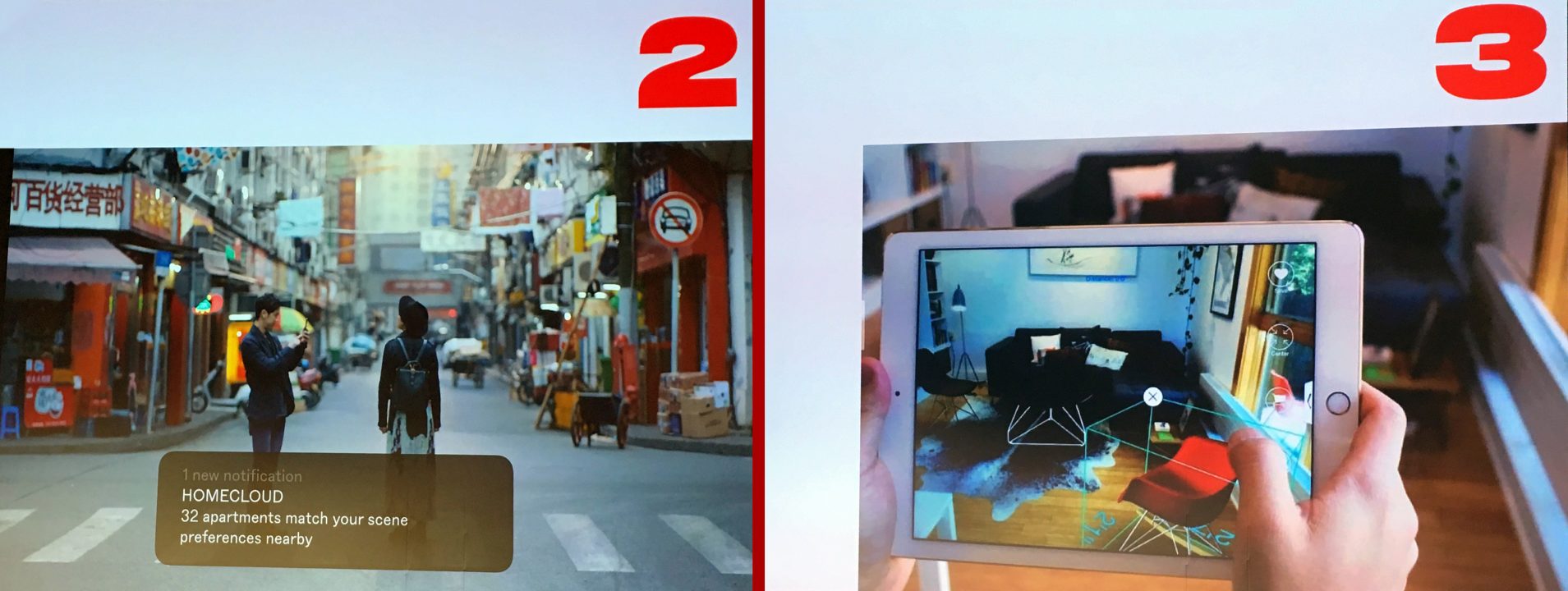

How do the structure and use of a city change as sharing economy flourishes? How can this economic order be applied to moving house and domestic environments? Can housing become an infrastructure of the city?

Lucia Tahan’s project Cloud Housing analyzes how technological platforms affect urban space. Sharing economy applications with unlimited options allow a lifestyle that is free from ownership. Considering this, Lucia is developing a prototype for a subscription moving app called Homecloud as a service and an infrastructure, thus designing an interface of homes as experiences. The project offers political and societal predictions and criticism through the concept of shared space.

Users who have subscriptions to Homecloud have year-round access to flats/houses that are ready to move into. They select a new house from the app and on moving day leave their current dwelling in the morning. Their new house will be waiting for them in the evening with everything moved and assembled. They can follow space creators, discover homes with high ratings, preview a house with augmented reality, and be free to live in any listed space.

Lucia predicts that if this way of housing becomes popular, instant gentrifications of neighborhoods will occur and the real estate industry may become volatile. How the threat of invisible labor behind Homecloud and similar apps (such as recent news about Amazon employees‘ working conditions, insufficient compensation, and grim treatment) will be incorporated into the presentation is also intriguing.

When asked why take out the process and go straight to the product, Lucia responds that the experience of moving is considered a burden, similar to carrying grocery bags (solution: Amazon Fresh) or renting a car (solution: Uber). Although the project aims to tailor the experience to the user, it is also aware that the risk of standardization of rented spaces and objects is very high. Feedback for the project included mentions of standardized product manufacturers such as Ikea and augmented reality apps that allow the user to try an item in the space for which it is purchased. How the app can provide an architectural experience rather than being a virtual furniture display and the risk of the prototype being realized in Silicon Valley and losing its critical attributes were also discussed.

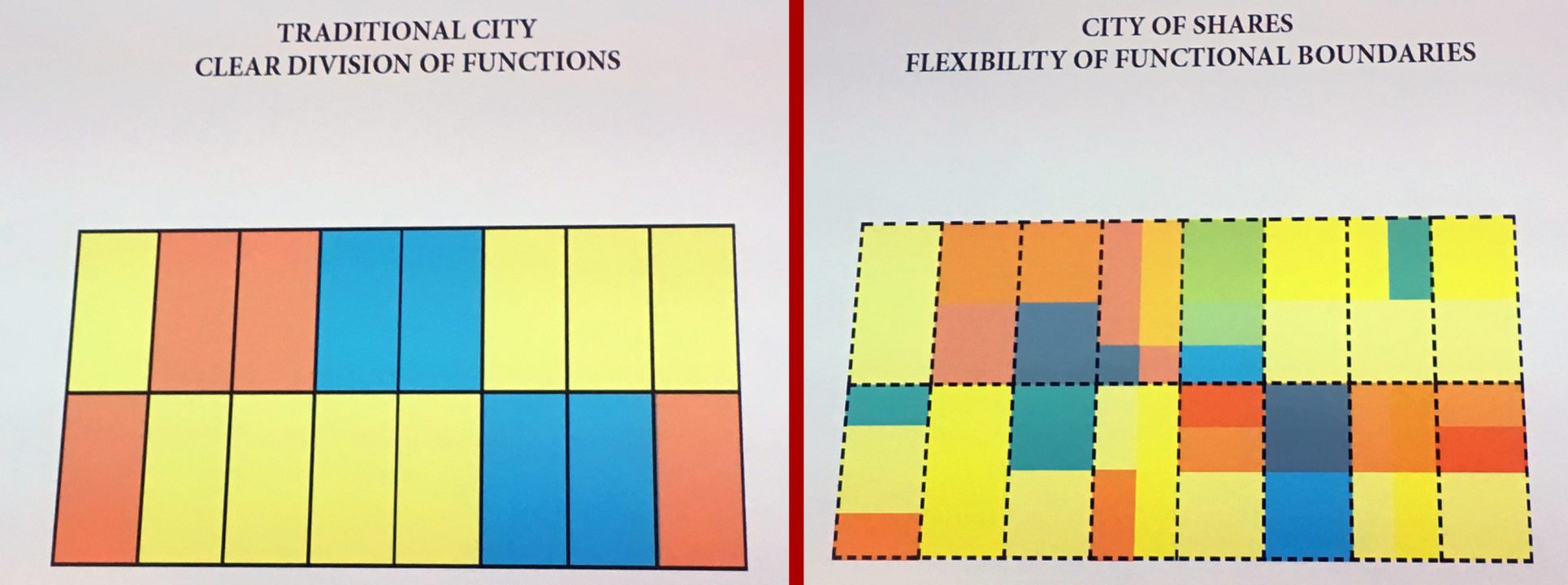

What happens when users share an entire city? How does a city react to this change? How does architecture react to this change in user behavior?

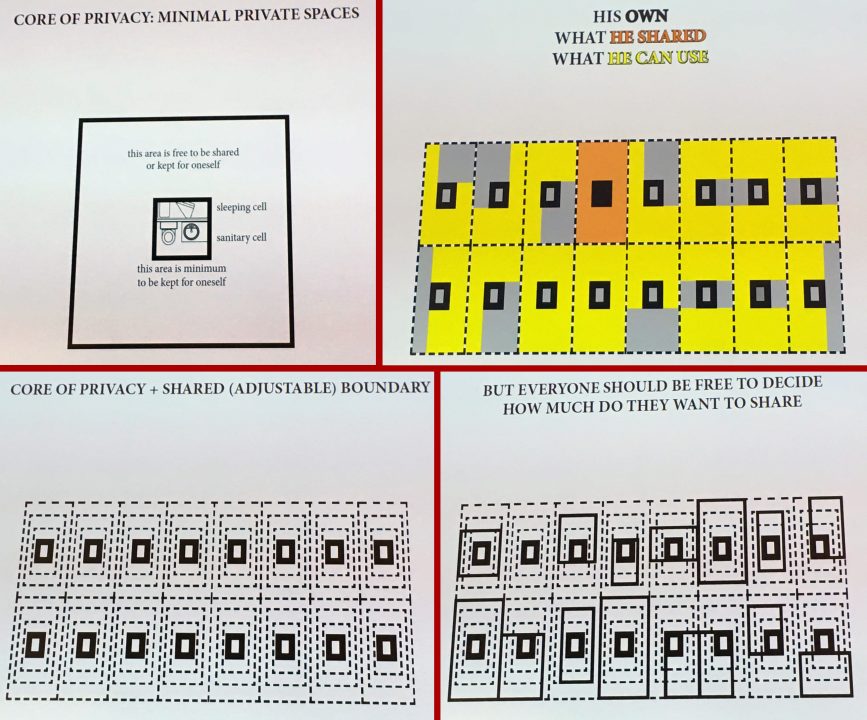

Artem Kitaev’s research Three Pillars of a New Home, has evolved into a study of variations in the organization of private and shared spaces within a city. Titled City Shares, his presentation suggests a new way of ownership and sharing, similar to the way in which spaces are used differently by each user in sharing economies. The project proposes a city that consists of various configurations of spatial units that have private spaces in their core surrounded by shared spaces with flexible boundaries. Without disregarding the need for minimum personal space, a landowner can use other shared spaces proportionate to the size they share. This leads to urban space becoming, in a manner, currency.

In Artem’s proposal, the rigid boundaries present in traditional city formations become blurred and flexible. The higher the rate of flexibility and change within space, the more contemporary a city is. Artem is trying different configurations of the determined boundaries of space (functional, visual, and acoustic boundaries; as well as heating and security) and experimenting with the ways in which the city organically forms patterns with these spatial organizations. The next step in his process offers flexible city layouts and sensitive boundaries rapidly responding to its users’ needs, which will eventually lead to a city in flux, with ever-changing manners of public use.

How do romantic relationships, the core that makes a home, affect parameters of domestic life? What are the needs of unconventional relationship units in space? Can spatial user behavior of non-monogamous relationships prompt new ways of domestic design?

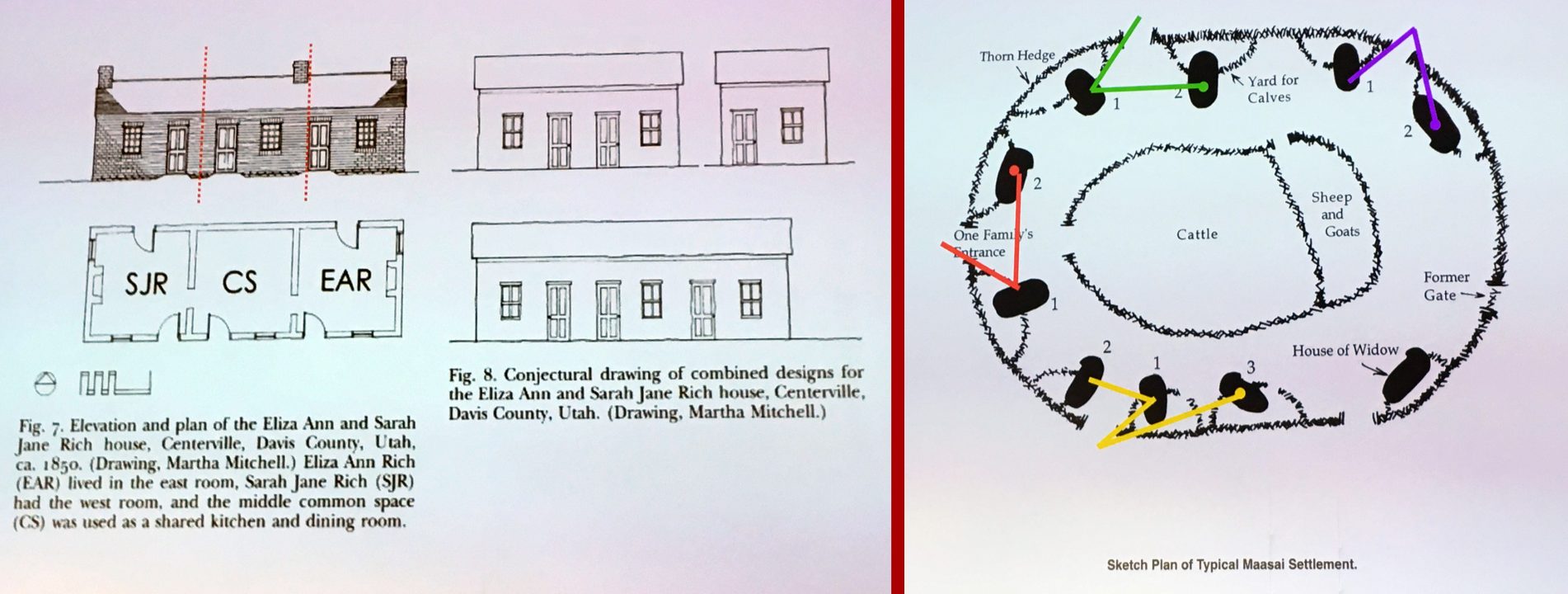

Dasha Tsapenko has abandoned her initial methodology of twenty case studies in her project Lovaratory, which focuses on how humans in alternative relationships behave in domestic spaces. Currently, she is focusing on analyzing various non-monogamous relationships‘ use of space and from her findings, proposing new housing typologies and methods of making predictions about future human habitats.

Tsapenko explained her thought process, detailing polygynous families‘ living spaces and circulation behavior through Mormon residential architecture examples, and the Maasai (an ethnic group local to central and southern Kenya and northern Tanzania) spatial behavior in their settlements. Now she intends to achieve a prototype through basing her work on closets, but she is mostly sure she will change her mind before the next presentation. She enjoys the ups and downs of her process, knowing that’s what makes it efficient. Lovaratory is an ambitious proposal that was presented at a critical point in its research process when ideas and methods were ambiguous. Nonetheless, the project will certainly lead to valuable information regarding behavioral, architectural, societal, and political aspects of non-monogamous relationships.

Housing the Human does not necessarily expect a final product from the designers. Rather, it values and encourages the design process, which is shaped by interactions with the local public and established experts at various locations. This “learning through the design process” approach was the theme of the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial, A School of Schools. In emphasizing the artists’ processes rather than the exhibited items, the biennial was a learning environment for both the artists and the visitors, a natural fit for Housing the Human. The collective, in-depth debates around these issues and the examinations of changing forms of housing and domestic life are more valuable than the final product. Ultimately, Housing the Human is a new form of school in itself.

The next stop for Housing the Human is the Copenhagen Architecture Festival in early April 2019. The designers aim to present the first versions of their prototypes at this event.